Excel error codes are sadly a part of life when writing formulas and functions, particularly as those formulas and functions get more complicated.

In the post below I hope to discuss:

- Excel error codes;

- the principle of error handling and why you should look to implement it in your custom functions;

- an approach to implementing error handling in

LAMBDA()functions; and - a custom function you can use to help implement error handling in

LAMBDA()functions.

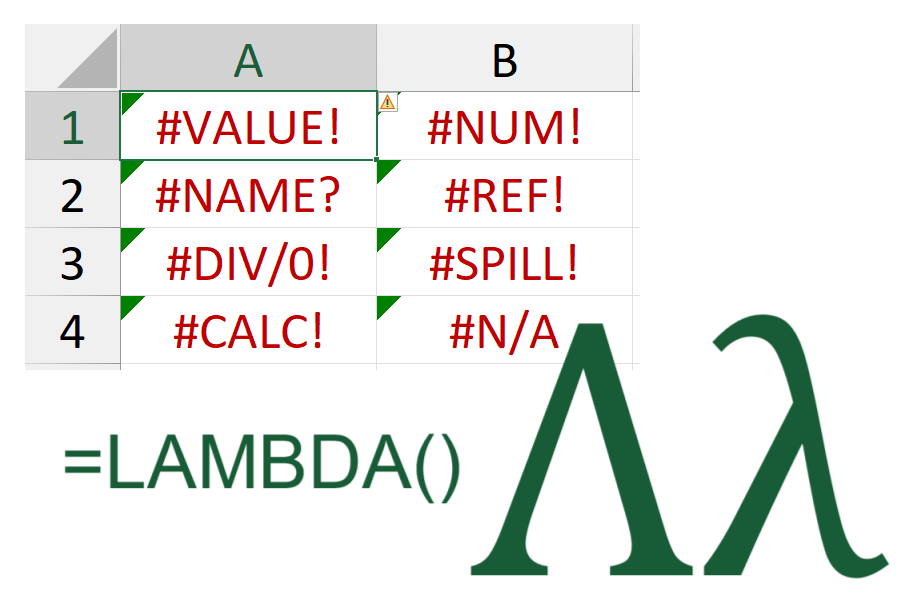

Excel Error Codes

There are a set number of official Excel error codes (19 in total as far as I can tell), known as ‘# values’ as they all start with a ‘#’ character followed by some uppercase letters to indicate the type of error. These are more intuitive for the user to understand than VBA error codes, which are a number with an often vague description, but can still be challenging to interpret.

Some important pros of Excel error codes include:

- consistent and recognisable way to indicate to users that an error has occurred in a calculation

- recognised as a special error object and treated in a unique manner by Excel and VBA

- therefore, errors can be picked-up/found by Excel (e.g. Find functionality) or by 3rd party add-ins

- errors propagate through other dependent formulas and can be traced back

The potential draw-backs of Excel error codes include:

- they are short text strings and as such are not very descriptive

- there are a limited number of codes, so a single

#VALUE!error from a complicated, nested formula can result from any one the of inputs within any of the nested, and dependent functions within a single formula - one error code resulting from a formula can lead to a different error code resulting from a dependent formula

These potential draw-backs can make debugging an error in a formula quite a difficult and potentially frustrating task.

Error Handling

Error handling is an important concept which allows the code author to monitor for expected or potential errors when code is run and deal with any errors in a controlled manner. This often includes dealing with calculation errors at important stages in the process, as well as user inputs/interaction.

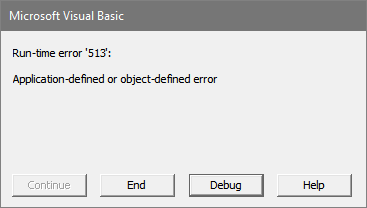

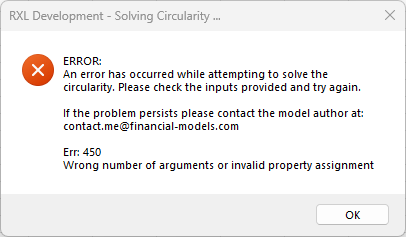

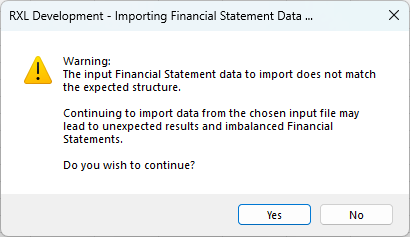

When working with VBA, any unhandled errors can lead to Excel crashing out or to the dreaded VB Editor (VBE) ‘Debug’ window appearing. Although the VBE debug window can be useful when unexpected errors occur during development, it does not look very professional when releasing a finished project to a client and could lead them to worry about integrity and completeness of the rest of the file.

For VBA code it is possible to provide quite extensive error checking at all stages of code execution and you can set professional looking and informative message boxes to appear if the user provides an invalid input, the workbook structure is not as expected, or an error has occurred. This makes the whole project seem much more professional and polished and you can also provide additional information to yourself within the message boxes or an error log which will help when the client calls you wanting advice or a fix.

Error handling with Excel formulas is more complicated as it is not possible to interrupt formula execution with a message box and get the user to provide valid inputs or make a decision about how to proceed correctly.

Most native (in-built) Excel functions will return a single error code when an error is encountered, although this can be more complicated where dynamic arrays are concerned. There is documentation available from Microsoft to help users interpret what may have caused the returned error code for each function, but as there may be multiple causes for the same error code, it can still be difficult to work out what’s causing your error.

Error Handling in LAMBDA() Functions

My approach to error handling LAMBDA() functions depends on whether the function is a custom function that is expected to act like an in-built Excel function, or a one-off LAMBDA() function that is not intended to be re-used or flexible, in which case error handling is probably unnecessary.

For re-usable custom functions, I use a LET() function within the LAMBDA() function immediately after the parameter declarations. This allows for testing the inputs provided by the user against expected data types, a required data range or data value(s). The following Excel functions can be really useful here:

ISBLANK()– checks if the input is a blank value / blank cellISNUMBER()-checks if the input is a numberISNONTEXT()– checks if the input is a data type other than a text stringISTEXT()– checks if the input is a text stringISREF()– checks is the input is a valid cell referenceISLOGICAL()– checks if the input is a TRUE/FALSE (Boolean) value

If an input check test fails then a flag variable (usually _inpChk) within the LET() function is flagged either with an error message or an error number. Having performed the rest of the function calculation the last part of the LET() function will check if the _inpChk has flagged in which case the appropriate error code or error message is returned by the function, otherwise the calculated result is returned (see the two examples below).

Example of input checks returning chosen error codes:

= LAMBDA(

cell_ref,

multiplier,

LET(

_inpChk, IFS(

NOT(ISREF(cell_ref)), 2,

OR(NOT(ISNUMBER(cell_ref)), NOT(ISNUMBER(multiplier))), 3,

TRUE, 1

),

_rtn, cell_ref * multiplier,

CHOOSE(_inpChk, _rtn, #REF!, #VALUE!)

)

)

Note: For the example above, the

IFS()function in lines 5-9 perform the input value checks.First (line 6), the

cell_refparameter is checked to ensure it is a valid reference; if not,_inpChkis set to a value of 2.Second (line 7), both the

cell_refandmultiplierparameters are checked to ensure they are, or evaluate to, numeric values; if not,_inpChkis set to a value of 3.Lastly (line 8), if the preceding checks pass, then by default

_inpChkis set to a value of 1. TheCHOOSE()function at line 11 will return the calculated value if no input checks flagged (i.e._inpChkwas 1), otherwise it will return a#REF!error code if_inpChkwas set to 2, or a#VALUE!error code if_inpChkwas set to 3.

Note: When directly typing a

LAMBDA()function with the#REF!error code in the Name Manager or a cell, there will be no problems. However, the Excel Labs Advanced Formula Environment (AFE) will not save a function which contains a#REF!value directly, so instead you can create a#REF!value if needed using INDIRECT("").

Example of input checks returning custom error messages:

= LAMBDA(

cell_ref,

multiplier,

LET(

_inpChk, IFS(

NOT(ISREF(cell_ref)), "#[Error: cell_ref must be a valid cell reference]",

OR(NOT(ISNUMBER(cell_ref)), NOT(ISNUMBER(multiplier))), "#[Error: inputs should be numbers]",

TRUE, ""

),

_rtn, cell_ref * multiplier,

IF(_inpChk <> "", _inpChk, _rtn)

)

)

An important consideration is whether to return an Excel error code from your function or a custom error message. It is also useful to consider a hierarchy of errors, i.e. which error is the most important in which case error that is returned above other error types. This will avoid providing a daunting list of errors to the user and encourage the user to fix the more important error first, but also leads to the potentially frustrating scenario of fixing an error, only for a new error code to appear instead.

When deciding whether to use Excel error codes or custom error messages for error handling in your custom functions, it can be useful to consider the following:

- Excel error codes

- easily recognised by (most) users as an error

- can be picked-up as error values by Excel and 3rd party add-ins

- will be treated as native error values by Excel and 3rd party add-ins

- not very descriptive of reason for the error

- requires additional documentation to assist user in debugging the error code

- Custom error messages

- can be as short or long as required and so can be very descriptive as to the reason for the error

- can create and use a standardised and custom message style for consistency

- may not require additional documentation to help user debug any errors produced

- will not be recognised by Excel or 3rd party add-ins as an error value

- may not be recognised by users as an error value, especially if the function is expected to return a text string

- longer error messages may be truncated or hidden by surrounding cell data

CErr (Create Error) Function

A flexible method for creating and returning native Excel error codes is to use a custom LAMBDA() function which contains methods for creating the required error code based on an input number.

= LAMBDA(

// Parameter definitions

error_number,

// Main function body/calculations

LET(

_err, error_number,

// Input value checks

_inpChk, IF(

// Check that a numeric value has been provided as the function input

NOT(ISNUMBER(_err)), "#[Error: invalid input]",

// Check that the number provided is within the required range (1-to-14) and is a round/integer value

IF(

OR(_err < 1, AND(_err > 14, _err <> 19), MOD(_err, 1) <> 0), "#[Error: invalid input]",

// If no input value concerns, return an empty string

""

)

),

// Calculate the return value

_rtn, IF(

// Attempt to match the provided number to the hardcoded list of supported error numbers

ISERROR( MATCH(_err, {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,13,14}, 0)), "#[Not supported]",

// If the match is successful return/create the correct error code

CHOOSE(_err, #NULL!, #DIV/0!, #VALUE!, INDIRECT(""), #NAME?, #NUM!, #N/A, #GETTING_DATA, , , , , LAMBDA(0).a, LAMBDA(0))

),

// Check if an input error message has occurred otherwise return the error code/message

IF(_inpChk <> "", _inpChk, _rtn)

)

)

There are 19 Excel error codes that I am aware of, however the following are not supported by the CErr() function:

#SPILL!= not supported as this error relates to worksheet structure and array dimension issue rather than a function calculation issue#CONNECT!= not supported due to difficulties with re-producing this error in a robust and repeatable manner#BLOCKED!= not supported due to difficulties with re-producing this error in a robust and repeatable manner#UNKNOWN!= not supported due to difficulties with re-producing this error in a robust and repeatable manner

#PYTHON!= not supported as this error is intended to relate only to errors from thePY()function; therefore could cause confusion if used with a non-PY()worksheet function

The CErr() function produces the following output:

| error_number | Result |

|---|---|

| 1 | #NULL! |

| 2 | #DIV/0! |

| 3 | #VALUE! |

| 4 | #REF! |

| 5 | #NAME? |

| 6 | #NUM! |

| 7 | #N/A |

| 8 | #GETTING_DATA |

| 13 | #FIELD! |

| 14 | #CALC! |

As the CErr() function is designed to produce an Excel error code/value, any function errors (i.e. an invalid input value) will result in a custom error message so that it is clear that the function is not working correctly.

If you want to use the CErr() function in your own projects or custom functions, please use one of the below options:

- Using Excel Labs Advanced Formula Environment (AFE) download the function using the Gist URL https://gist.github.com/r-silk/8ca0742d549ec4153d403b0a64847974

- Alternatively, go to the GitHub repository https://github.com/r-silk/RXL_Lambdas and download the file

RXL_CErr.xlsx- this file contains a copy of the function in the Defined Names which can be copied into your own file

- there is also a “minimised” version of the function which can be copied and pasted directly into the Name Manager when defining a new name of your own — please use the suggested function name of

RXL_CErr - the available file contains the documentation for the function as well as some details on development and testing/example usage